Atlas Network: When Racism Pays

How anti-indigenous movements are crucial to the neoliberal machine.

The one common feature of Atlas’s globe-spanning campaigns is the racism.

Oh sure, they’ve stoked xenophobia in spades across Europe (The Atlas Network Is Also Targeting Europe), riled US conservatives on social topics like abortion, and they’ve got a pretty worrying track record of influencing anti-protest laws and demonising climate protestors wherever they go. But none of this is quite on the scale with which they hate, hate, HATE indigenous peoples and their claim to and protection of the single thing the super-rich want to exploit more than anything: the land.

It must be really, really frustrating to be denied something when you’re a billionaire business tycoon who can do pretty much anything you want when you throw enough money at it (And you definitely have enough money, because you’re a billionaire. Take Elon Musk’s little tantrum, for example: if it costs less than Twitter, for the truly wealthy, it’s chump change.) There’s next to nothing you can’t get away with when you own the media or you know the guy who does, and you can afford to buy off whoever you like, and the last three whistleblowers who tried to expose you all died conveniently in their cell. At this point, you’d think you might be twirling a villainous moustache and practicing your maniacal laugh with your feet kicked up on your oversized executive desk. These cliches don’t just fill themselves!

But alas, you are not happy. Every time you create a scheme that will vastly improve your wealth via a mass extraction of resources from the earth, some annoying little people who should have barely been speed bumps on the road keep blocking your project entirely. These Native American tribes won’t let you put a massive leaky oil pipe through their lands. Indigenous groups in Canada keep kicking up a stink about a decaying oil and gas pipeline that could burst and “wreak environmental havoc at any moment”. And the Sami are, for some strange reason, really against their ancient forests and grazing areas being destroyed and so have teamed up with environmental activists to stop it.

That’s not how neoliberalism is supposed to go! The free market is making you a lot of money (Man, wasn’t that a good idea??) and whenever oil pipelines are blocked or forests are preserved, those are the mechanisms of industry that could and should be turning to make you richer, now instead just sitting there sinking carbon or something. That’s not profitable! (Yet.) But everywhere you turn, people seem to be getting annoyed about you doing destructive things on “their” land. Don’t they know how rich you are??!

This is really quite inconvenient for you, and it’s starting to be a real bummer. It’s a big deal, an absolutely massive deal, the biggest deal that’s ever been dealt because you’re a billionaire and are therefore the world’s biggest baby, and anything that stops you getting your own way must be destroyed. And if that includes the climate and thousands of different pristine environments, so be it.

You need more money. For some reason.

Thatcher: The Canary In The Coal-Mine

In many things, Thatcher did it first; most notably, neoliberalism. A lifetime admirer of Hyek, she became the first leader ever to institute a regime of what we now know as neoliberal economics, influenced deeply by the Mont Pelerin Society, the precursor to and creators of the Atlas Network. Thus, Thatcherism was born, becoming the template for economies across the globe.

But not only did she pioneer our economic system, she pioneered what Atlas and the Kosch brothers have positioned in direct opposition to it: climate change activism.

“Tree-hugger Margaret Thatcher” isn’t exactly the leading image she’s left behind, but it’s true — for some years while she was in Parliament, she was a staunch advocate for measures to combat climate change and she spoke passionately about the need for economic and environmental progress to work in tandem on combatting these issues.

This was a problem for neoliberalism that needed to be neutralised. By all records, Thatcher was provided with a long list of reading to convince her otherwise, one of which was funded to the tune of $70,000 by Exxon Mobile. But it was a 1997 pamphlet published by the Reason Foundation — now right-wing US news site reason.com — that brought her back to her conservative senses, and by 1998 she was attacking climate change and Al Gore as socialist conspiracies both once more.

How they do it

Neoliberalism is a well-chosen name; it is not just economic liberalism, but the promotion of individualism at the expense of collectivism. The Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), which published much of the propaganda that laid the groundwork for Thatcherism, understood well the need for a shift in overall public cognition on these issues and worked to change it. IEA literature talked about how, “an understanding of the moral foundations which government acquisition and holding of property, the right of the individual to have access to free competitive markets and the necessity of a secure and honest monetary system” could cause a call for change,

While the phrase “the right of the individual to have access to free competitive markets” is an oxymoron and an hair-raising “right” to be pushing, it demonstrates that cultivating a certain mentality was as important to Atlas as wide understanding of the underpinning economic principles. It’s necessary for neoliberalism that individuals be primed against collectivism so they may embrace the individualism that is inherent to the doctrine; in this way, neoliberalism benefitted richly from the “Red Scare” that the right worked to make scarier.

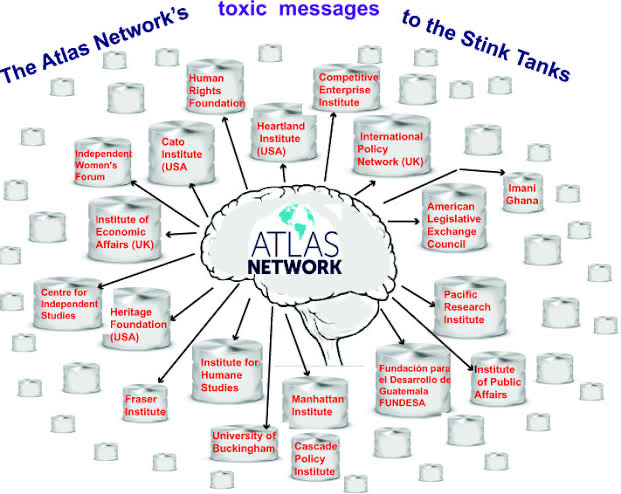

Think tanks don’t create economic change out of nowhere, they wait for conditions that signal change is coming and then give it a little push in the direction they prefer. For this to be as effective as possible, they also usually lay the groundwork and build social momentum that can propel that change. They get in ahead, years ahead, publishing research that supports their general ideals of economic individualism and free-market dominance and — crucially — how that might fit in with an existing society and economy. That is the purpose of the New Zealand Initiative, to apply free market ideals to New Zealand, as it is the purpose of all the other baby kiwi think tanks it’s birthed like academic Russian dolls. By the time a person like Thatcher comes along, the positions the public and politicians will be taking has already been established from the “economic education” distributed by a range of right-wing think tanks in the years prior as they get the country familiar with concepts they wish to see implemented.

That’s why New Zealand’s neoliberalism was instituted by Labour. It isn’t just conservative politicians the Atlas Network seeks to convert and shift to the right: one-time centrists like Winston Peters and liberal lefties from within the Labour Party itself were all fair game too. Although the economic theory was right wing and described openly as such by all who produced it at the time, it did not need a right wing politician to bring it to life; it needed only strife and crisis. And Roger Douglas.

Thus New Zealand was the global demonstration of the Atlas Network’s true insidiousness. They did not just prepare our conservative politicians to push neoliberalism, but the left too, and they prepared them so thoroughly and placed their neoliberal-influenced politicians so well that it only took one man to become Minister of Finance for the country to fall to the neoliberals.

Materials written by the IEA itself discusses how successful they were at converting Labour politicians in the UK, but nothing can be a more shining success than our own Rogernomics, the right wing wealth-gap creator introduced by the Labour party.

Perhaps the indoctrination of Roger Douglas was merely intended to ready him to show support for right wing politicians preaching neoliberalist values, or perhaps they counted on Douglas crossing the floor (which he sort of did do afterwards when he creating the once-center-right liberal ACT party that has shimmied itself along the spectrum and now is leading the charge in Atlas’s agenda against indigenous rights).

Or perhaps they got lucky.

If their intention was only ever to stoke left support for their policies, they must have been amazed at their own success. However you count it, Roger Douglass was the best investment the Mont Pelerin Society ever made.

That’s the important thing Atlas analysts are missing: New Zealand was never going to escape neoliberalism, not when it was introduced by the left and eaten up by the right. Nor was any other country. If it hadn’t been Reagan, hadn’t been Thatcher, it would have been someone else; it would have been everyone else. Other politicians who’d read their pamphlets and attended their conferences and benefitted from their connections and attention and saw what was going on globally and liked it. After all, they’d all had these ideas disseminated and sold to them. The charge that was led loudly by Thatcher could have been a slow inevitable overrunning instead, had the Iron Lady not been made of enough iron to build it all herself. But Thatcher was exactly the sort of person they had sought to convince.

And convince her they did.

Bending the Iron Will

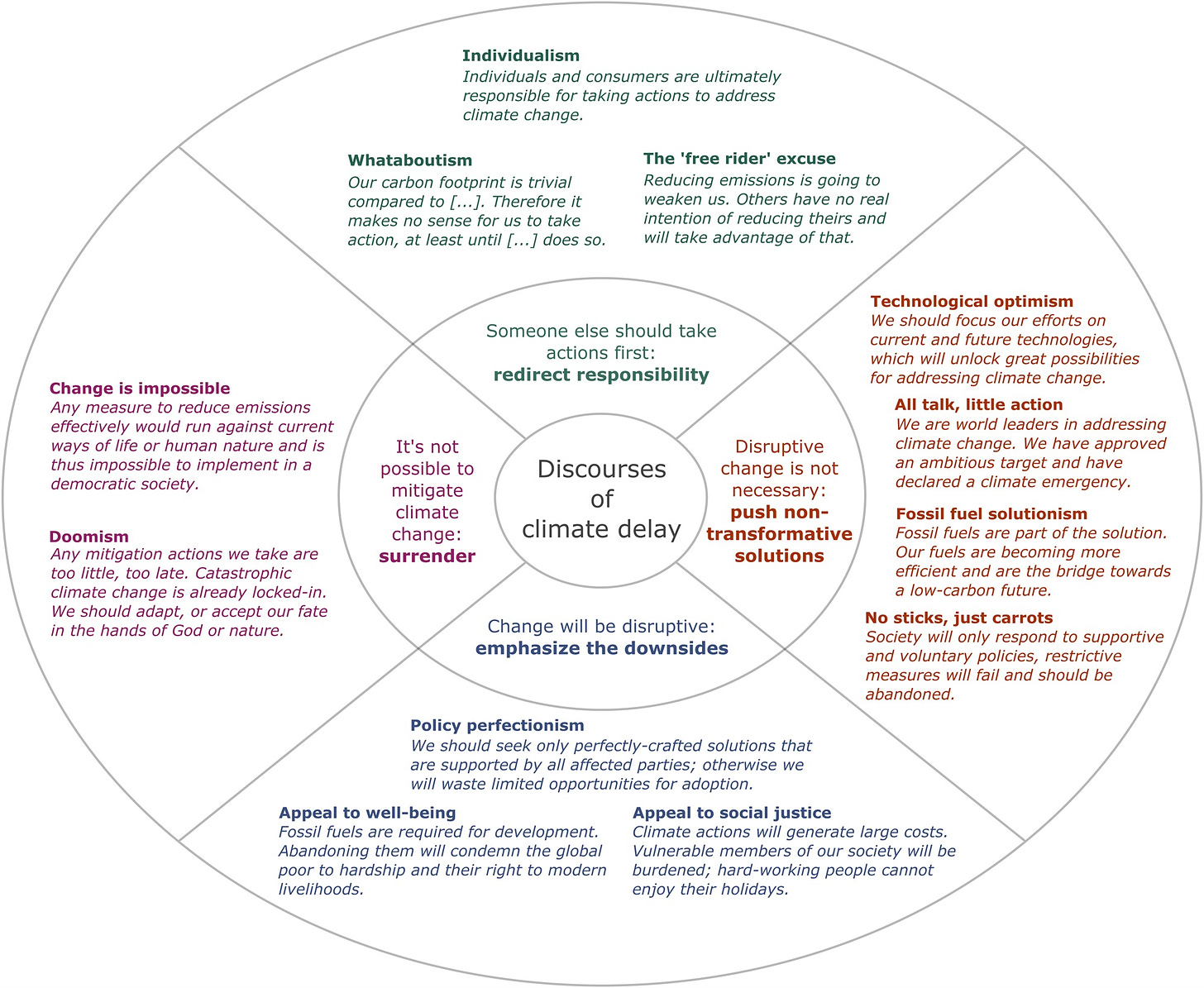

Environmentalism and the free market are fundamentally opposed. There is little to no economic value placed on many crucial things like ecosystems and “the ability of the planet to support life in the future”. Meanwhile, efforts to mitigate climate change drain the profits of big businesses (whose shares are owned by the wealthy) and challenge the very concept of individualism that neoliberalism pushes so strongly. We can all do whatever we want, all the time, and the market will sort it out! That’s why we have climate credits, so businesses can still pollute and they’ll just pay dollars for it, thus creating a market that regulates our emissions.

Except we’re still emitting.

This is a very deliberate tactic these think tanks use: delay and distract. Consumers and activists and politicians can be tricked into caring about things that make overall little-to-no difference to the environment, and most importantly, they do not threaten to introduce any sort of structural or systematic change. That is why Exxon funds Atlas, and why it has spent billions of dollars over the past forty years funding climate denial and promoting ineffective ways for people to help the climate, distracting consumers with concepts like their “personal climate footprint” and producing and promoting literature that suggests consumer energy saving measures make a difference to the environment.

But it is much harder to distract people from the massive oil pipe you want to install in their backyard, or the fracking on their ancestral lands.

Community opposition is one thing. That is expensive enough and slow enough and difficult enough to tackle already, if you’re a massive corporation intent on doing awful things. But these indigenous groups have genuine moral, ethical, and, crucially, legal claims over the land that the capitalist machine and the corporations that make it up want to exploit.

There is only a small window left to sell as much oil and as many oil-based products as they can before we will transition away from this energy source, and we have already passed the peak of it (barring outside interference). At this point, any exploratory drilling will be finding oil fields that we won’t be able to access until well into when oil is being phased out. Investing in a declining resource is a bad idea, but the rich have quite a lot riding on the entire concept of oil at this point, and the industries that are in danger will protect themselves and be protected by their investors in turn, because to not exploit something that is exploitable goes against the entire ethos of the free market model.

Thatcher had realised, with a lot of help from her intellectual sponsors, that the end result of climate activism and the end result of neoliberalism were fundamentally contrary. Neoliberalism cannot work without over-exploiting the planet, and therefore to Thatcher’s mind, climate activism was unable to proceed without detrimentally limiting neoliberalism in a way the ethos didn’t really allow for. Unable to reconcile this with flaws in her economic thinking, Thatcher blamed the socialists after eating up some delicious propaganda and returned to her comforting worldview that individualism trumps all, and that wealth generation is the ultimate goal (that left-infiltrated climate activists only wanted to get in the way of, of course. Damn commies!)

To neoliberalism, to corporations, and to Atlas, individuals with vested interests in the land and environment must be neutralised. This is difficult enough when the stakeholders are a town or community that will be affected, or it’s just one person (who is also the Prime Minister of England and who surprisingly doesn’t want to see the planet burn, contrary to any other indications she’s given out). But for the most part, like Thatcher was, these groups and people are easily put off or distracted or swayed to your side.

Indigenous groups are a lot harder to dissuade or pull the wool over their eyes. They already have a greater longer-term interest in land being preserved than, for example, a township, because of their much deeper ties to the area, ecology, history, and the overall wellbeing of the land. Tribal groups are permanent blockades; they cannot be convinced to move away and are less likely to be persuaded by literature disseminated by think tanks attempting to convince them that unmitigated destruction is the best way forward.

That does not stop Atlas from trying. One of Atlas’s many strategies for dealing with native objectors is to employ indigenous individuals sympathetic to their economic thinking and use them to promote ideas like “The future of indigenous people relies on them exploiting their land”. They have had such success with this strategy in Canada they are now rolling it out to the Middle East and Africa, pitching neoliberalism to the people and investing hard in economic “education” as the only solution to their poverty crisis. The Western world has borne the benefits of the free market, says Atlas; now it is time for the third world to do so too.

That would be pretty convincing, if you were the third world.

Atlas has discovered a huge number of ways to undermine native activism and the inherent claim they have to their lands that keeps them invested in preventing its exploitation. It claimed success in 2018 and 2020 when its partner organisation prevented the Canadian government from supporting the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous people, something they had fully supported ten years earlier. UNDRIP would have confirmed the sovereignty of indigenous peoples and given them right of consultation over large-scale projects that affect their lands.

I should clarify here that Atlas doesn’t care who is exploiting the land, per se, though you’ll generally find it’s a big industry corporate ally like an oil company that is doing the job. But really, Atlas just cares that it’s being exploited; that restrictions placed on environments are not impeding their ability to make money from the larger economic machine that they own many parts of. In other words, that there as few restrictions on economic activities as possible.

Remind you of anyone?

Vested interests don’t need to own the land or be involved with the industry of extracting resources (though they usually do and are); what’s important to them is that productivity and industry is not impeded. If indigenous people were as happy to destroy the environment as corporations, there would be little issue. But time and time again, indigenous activists are the groups who most effectively blockade environmental destruction.

Nothing is a greater threat to resource extraction than the Land Back movement, which seeks to restore ownership and authority over their ancestral lands to indigenous people. Anything that gives indigenous people a say about land usage, even if it’s not the full power of veto, even if it’s not binding and can only give recommendations, is treated as a danger to neoliberalism and the free market — or as Atlas puts it, to freedom.

That’s why when Australia threatened to create an advocacy committee that would advise Parliament on indigenous matters, the Atlas network sprung into action. Public opinion went from majority in favour to deeply negative; the Voice campaigners would later admit they weren’t prepared to have to convince Australia so fervently that this was needed. And of course they weren’t — all evidence indicated that Australia was in support of this relatively conservative push for indigenous representation.

If the Voice scared Atlas, the Waitangi Tribunal must be a nightmare. Many of the greatest victories won by environmentalists have been through the courts, and there is a growing body of national and international law in a vast array of countries granting native peoples moral and legal rights over their own land. The Waitangi settlement process is 30 at least years ahead of its time, as well as being a judicial version of the Australian “Voice”: a court with investigative powers, their precedents now firmly set by a body of indigenous decision making they themselves have made. New Zealand quite literally had a world-leading relationship with its indigenous people, including legal rights and protections we have granted and enshrined — a claim we are perhaps only beaten to by the Sámi of Iceland.

We can see how effective the Waitangi Tribunal is as a watchdog in the saga over the many, many proposed bills it has deigned to investigate this year, but in particular their inquiry into the removal of section 7AA from the Oranga Tamariki Act. Despite having to investigate multiple matters at once in a shortened space of time due to the government overloading the schedule with fast-tracked legislation (in addition to the Tribunal’s normal workload), they pursued problems they identified with the government’s actions, including taking a breach of comity from the Children’s Minister to the Court of Appeal that gives us a fairly clear judicial indication that she was not acting in good faith.

Given how powerful it is, it’s perhaps unsurprising then that we have parties in our Parliament seeking to abolish the Waitangi Tribunal.

Another indigenous ownership issue that Atlas cannot abide by is shown in the dragging up of what was already a settled issue in New Zealand: the foreshore and seabed.

Petrol might be dying but mineral extraction never goes out of fashion, and the exploitation of our oceans is going to be a large focus of the next several decades. This is the controversy that first gave us the Māori Party back in 2004, so it is fitting that in 2024, they sit in Parliament now with the numbers and experience to advocate for Māori interests as they relitigate the compromise made between Helen Clark and Winston Peters that saw ownership of our foreshore vested in the Crown (rather than Dunne’s offer for it be owned by the public).

When Michael Cullen passed the bill, he claimed it would protect the foreshore and seabed for everyone. The irony is that the Crown is by far the weaker protector than tangata whenua. As Atlas and Mont Perin have demonstrated over and over again in the last seventy years, politicians are very swayable, and economic interests are very long-lived. People die; corporations do not.

But neither do iwi. And while there is undoubtedly a commercial interest they themselves have in their land that they can choose to exploit, the fact that it is their land makes all the difference. Residents of a town can move. An entire country will turn its attention away from a province eventually. Politicians can be bought and influenced and confused, and land-owners will sell and buy, and councils will get mired in layers of bureaucracy. All off these stakeholders should work to protect the land, but somehow this still hasn’t been enough.

But indigenous groups are uniquely positioned to act for the environment, for their little piece of the environment, in a way that overrides commercial interests (eventually — you can’t expect them not to engage entirely in capitalistic practices in a system of capitalism). This connection to the land is not bound by the finite time of human lives, and comes with an innate duty that cannot be unwritten by statute or overruled by the courts (though Atlas will try anything).

Indigenous rights, the right to protect their whenua, is the strongest protection we could possibly provide the environment against neoliberal interests. On a global scale, it divvies the world up into small parcels of land and assigns a small group to look after that one single piece with everything they have. And those groups then have the advantage of all the modern and ancestral connections that humans tend to form, within and outside of their group, including an existing intra-tribal social structure that can be quickly put to use. A small town trying to protect itself from a mining company needs to gather support and host meetings and fundraise and organise afresh, and while they are beginning, potentially before they’re aware there is an environmental threat, the community is vulnerable to misinformation and interference.

The pre-existing nature of indigenous relationships, the community already being linked by the land, the long-term connection to it, the tribal structures that already dominate their day to day; all of these factors make interference from bad actors nowhere near as effective as deploying propaganda against groups like residents. Reefton thinks their latest mineral find could make their fortune and “bring them back” from when they made their fortune off the coal industry, and they are correct, it could. But they are much more likely to blinded by the promise of profit and continued industry than a concerted collection of native peoples all working in tandem for the sake of their land would be, and a looser unit of people with a looser connection to the area can easily see division stoked or harms overlooked.

Atlas fears a world where, wherever they turn, the land is protected by people who love it. By entire groups of people who can call on and unite with other groups of people to help them defend it. Where international and domestic courts respect the rights of native peoples’ and their connection to their land that makes them such strong advocates. Some of our planet’s greatest known treasures exist on tribal lands, or what might be tribal lands — the Amazon rainforest being one of the largest and most profitable areas that is still inhabited by indigenous groups. That is why Atlas has such a strong presence in South American politics and lawmaking: to cut them off from protections they would otherwise be very likely get. Whereas in Africa, Atlas are trying to take advantage of the poverty the western world has left them in, attempting to convince them to follow in our footsteps and share in our spoils. To Africa, neoliberalism is being sold not as environmental exploitation, but quite literally, economic liberty.

And who could blame them for wanting that?

Yet there are still those who resist it. Who aren’t bought off by promises even of a better life for their people at the cost of the planet, and who’ve seen above the lies to the sustainable economical improvement that is possible. Many, many people and groups are working on initiatives that improve the lives of local people in impoverished parts of the world so that they can develop the independence to become sustainable protectors of their own land.

Atlas vs Maori

Atlas showed their hand with Australia’s referendum. They weren’t prepared, hadn’t laid the groundwork, and the resulting swing in opinion made it very obvious to all that there had been political interference in the referendum process. Atlas were disturbingly, disgustingly successful at influencing a democratic vote for their own ends and profits, but the outcome gave Australia pause, and it gave Aotearoa a warning we have used well.

After all, unlike Australia, we have done this before.

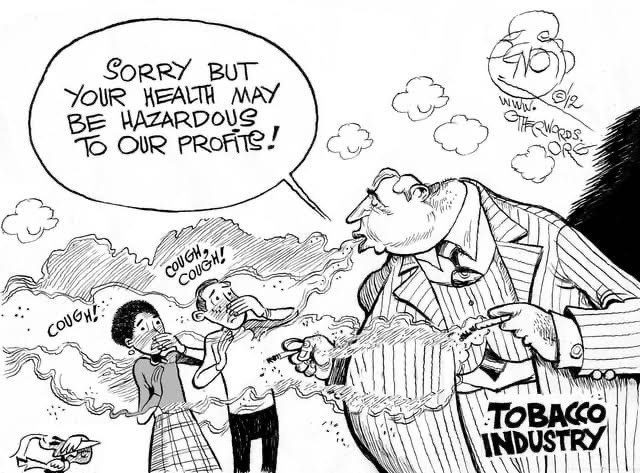

If you’ve ever wondered why suddenly our anti-smoking progress is being reversed when before it’s been such relatively smooth sailing, look no further than Atlas’s sudden and recent arrival to our shores, bringing with them decades of experience working alongside tobacco companies, where they paid donations to American politicians considering smoking restrictions, recruited journalists to dispute findings of the EPA, fought against the Clinton Health Plan, and used the IEA to disseminate ideas around trademarks that cast doubt on plain packaging initiatives.

“By funding multiple think tanks within a shared network, the industry was able to generate a conversation among independent policy experts, which reflected its position in tobacco control debates.”

Tobacco and crashing markets and Eurocentric anti-immigration racism are all well and good — Atlas will use it whenre they can. But nothing makes them sweep into a country, publications at the ready, like indigenous rights. It’s literally not enough for them that the Crown owns our foreshore and seabed and have already consented to projects that iwi wouldn’t have; that there is any room for a claim at all is a body of law Atlas do not want to let stand. This is a situation Atlas and the extraction industry are still unhappy with today, and they have stoked the issue through the Atlas-affiliated pressure group Hobson’s Pledge (started by, you guessed it, Jordan Williams, the father of the Aotearoa think tank) and now want to divvy it up more decisively to remove potential customary claims. While this legislation remains, any uncertainty over specific land rights will continue to see cases end up before the judiciary, the one branch of our government Atlas have had (as far as I’m aware) little success in infiltrating or converting to their ideals.

That’s exactly why we have three branches of government in the first place, and it is also why we have so much going on regarding the separation of those branches right now: interference with the judiciary where the Attorney-General has had to step in (more than once), Winston wanting to severely limit the Waitangi Tribunal , Members of Parliament are breaching comity, and ex-PM Geoffrey Palmer is sounding alarm bells over our constitutional soundness.

Atlas’s harmful policies all tie in together. The positions they take are all inextricably linked.

But it’s the anti-indigenous racism they’re really here for.

Racism sadly paid during the slavery and imperial eras, and it sadly still pays today in the form of racial profiling & indigenophobia.