Butter, butter everywhere and not a bite to eat

In which Nicola Willis may have accidentally claimed credit for actual price fixing.

National has become, to put it politely, a party of habitual liars.

Their favourite things to lie about are what they’ve done—or haven’t done. They are as quick to pin blame for the bad on someone else (Labour) as they are to claim credit for the good. It’s become eye-rollingly regular. It began at the start of their term with a celebration of a bridge built largely under Labour and has continued unceasingly into the present, where according to themselves, they have somehow simultaneously created growth that doesn’t exist while defeating the inflation beast (that already lay wounded and dying) by sending unemployment rates soaring to levels not seen since the Global Financial Crisis.

They just can’t stop the spin machine; can’t stop painting rainbows that don’t exist into our pastoral and polluted scenery.

Their latest lie of an announcement was for funding that had been generously tallied to include mostly previously apportioned money, including even more Labour initiatives they are making their own.

As such, when this government take credit for something these days, I rarely pay it much mind.

And National are in good company inside their coalition of collusion and illusion.

What is it that people keep pointing out about Donald Trump?

If you want to get away with a lie, tell a bigger one first. Then the smaller one doesn’t seem quite so outrageous.

National’s lies are simply good old-fashioned politicking next to David “making it up as he goes” Seymour, while Winnie’s deluded ideas about trans people being pedophiles and the media personally out to get him make Chris “Fricken” Luxon seem calm and serene by comparison.

Of this three-headed taniwha, Luxon’s head is definitely the doziest, and the Ministers who work beneath him seem free to do as they like.

And what they like to do is lie. A lot. It’s the perfect administration, if you hate democracy.

One claim, however, National made recently stood out to me as being not quite like the others. It comes with something so many of their supposed accomplishments are always lacking — evidence.

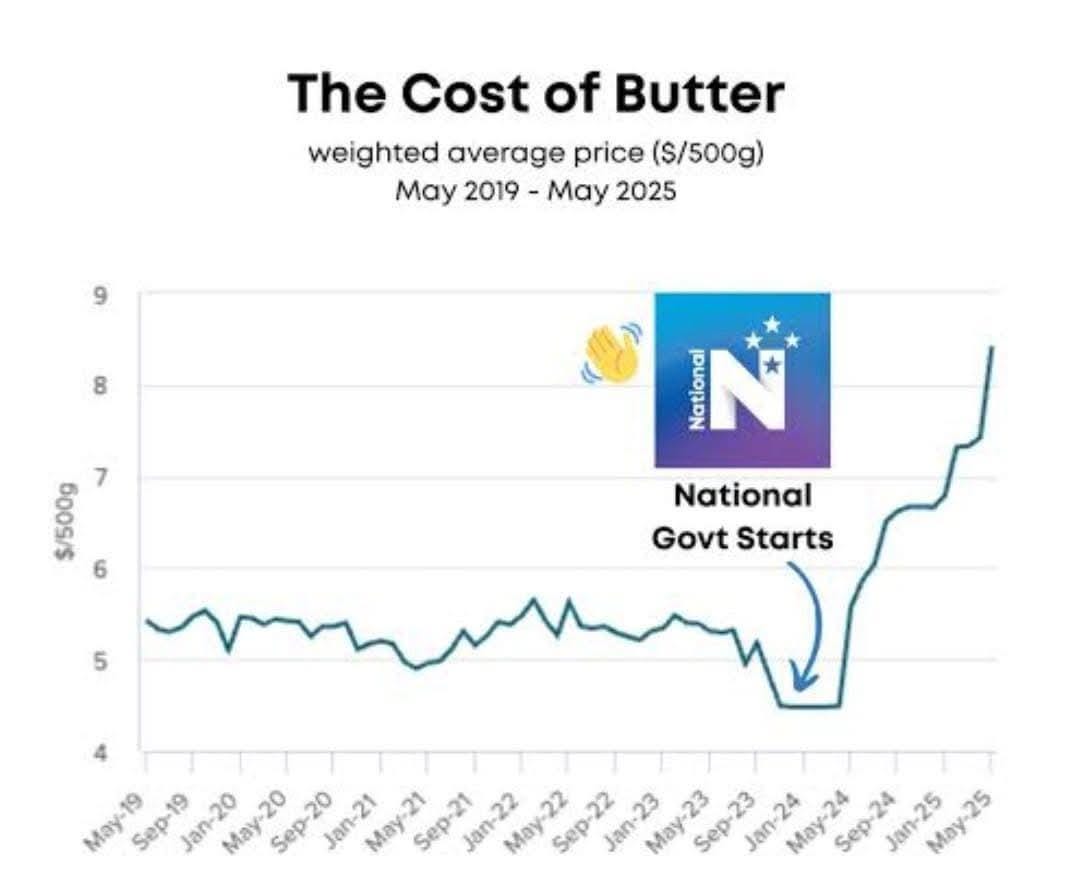

This screenshot on social media caught my eye.

[My understanding is that this was posted by National/Nicola Willis on Facebook, and they are/she is taking credit for the price of butter dropping and stabilising after taking office in October 2023. Unfortunately, the Reddit re-post I saw it on has already been removed, and if it was ever posted to National or Willis’s pages, it’s since been deleted, so I’ve been unable to verify this. But it was not the claim that caught my eye so much as the graph itself.]

I’ve taken to amateur economics of late. Much like astronomy and aviation, it’s a field better enjoyed as an amateur — more time spent marvelling at wonders, and less time spent doing the maths that makes it all work.

Like so many fields best appreciated as an amateur, economics is, when you boil it down, just a simple series of causes and effects.

Where butter fits into the New Zealand economy

‘Cause and effect’ creates everything; almost nothing is truly random, and nothing exists without cause, nor without creating effects, known and unknown. Even that which appears unattributable to our inexpert eyes is all too often not. ‘Unexplained’ does not mean ‘unexplainable’; ‘undiscovered’ does not translate to ‘nonexistent’ or ‘immaterial’.

This is good to remember when examining events on a macro scale.

Another good principle is that everything moves in cycles. What has been seen before will be witnessed again. Often while following some sort of pattern.

We are still caught in the death throes of post-pandemic inflation caused by the increased circulation from the loosening of fiscal constraints in 2020 (and beyond). This was a predictable effect; it was known that this would happen, planned it would happen, even, just as the recession later engineered by the Reserve Bank to restrain it was no secret or accident. But the effects of that inflation itself were not so well predicted or prepared for. Certainly not by the government that was brought in afterwards.

Loose fiscal policy creates increased market activity that profit-seekers will naturally use to seek profit; when that profit is sought first and foremost on necessities, in part due to government restrictions on things like physical recreation (think sourdough starters and the ebook boom), it will cause prices to increase, especially on those necessities that are already hit hardest. People can’t do without necessities, so consumers and companies alike are forced to fork out for higher costs, which in turn pushes inflation onto wages and secondary goods.

So the cycle spins out of control, and if left unchecked, it will continue to sweep up all the money people have left until there is no more.

And people have run out of money.

Recessions are caused by one thing and one thing alone: people not spending money.

People cannot spend money when they do not have money to spend.

This might seem obvious, but it usually actually takes economists quite a while to work out.

In assessing a recession, it‘s irrelevant to analyse how an economy got to this point (though we can take a few guesses). The only question that determines whether it continues is, “Do people feel like they have money to spend now? And are they spending it?”

The post-COVID inflation was people spending. They spent so much money that people were spending money they didn’t have—more so than ever before. They opened lines of cheap credit and renovated their kitchen, or built that big deck they’ve always wanted. They maxed out their afterpay account they didn’t previously have, creating brand new debt that wasn‘t widely available to kiwis pre-pandemic. No credit? No problem! You can use this deficit on top of whatever card you’ve already maxed out and sits accumulating interest.

And so many people do have both.

This was even more inflationary than adding cost onto necessities, inserting billions of dollars of debt (and cash) into our economy one small purchase at a time.

Now that people are feeling the pinch, those lines of credit look less well-spent.

But what about butter?

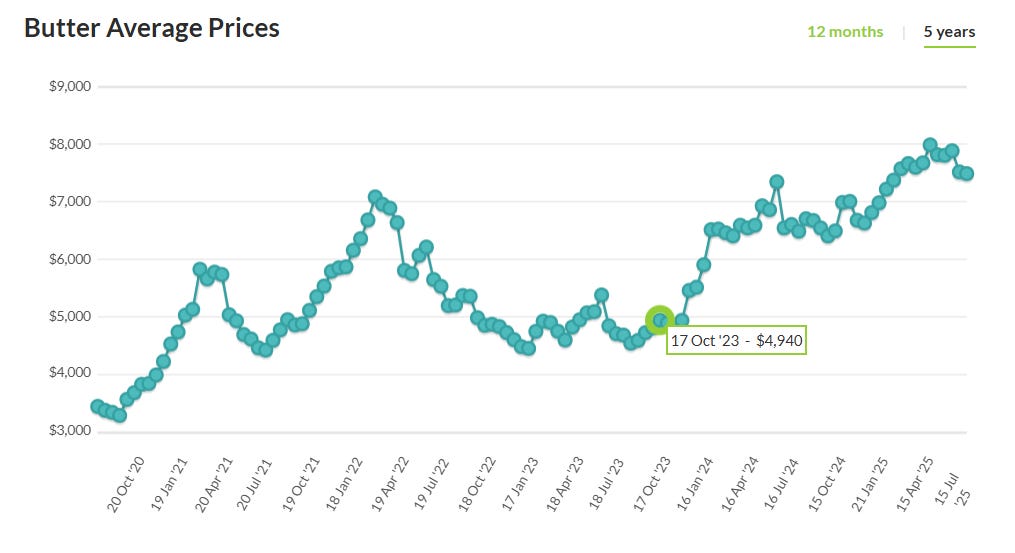

Butter prices in the US have been rendered very sensitive to the cost of fuel because as overheads increase for farmers, they prioritise the production of milk over butterfats since milk is more profitable to sell while butter requires a lot of processing for little profit. Breeds of cattle that produce milk flourish, while other fattier stock decline. This means US domestic supply of milk is right now still responding to oil shocks from some years ago while natural disasters and global tensions continue to exacerbate price volatility.

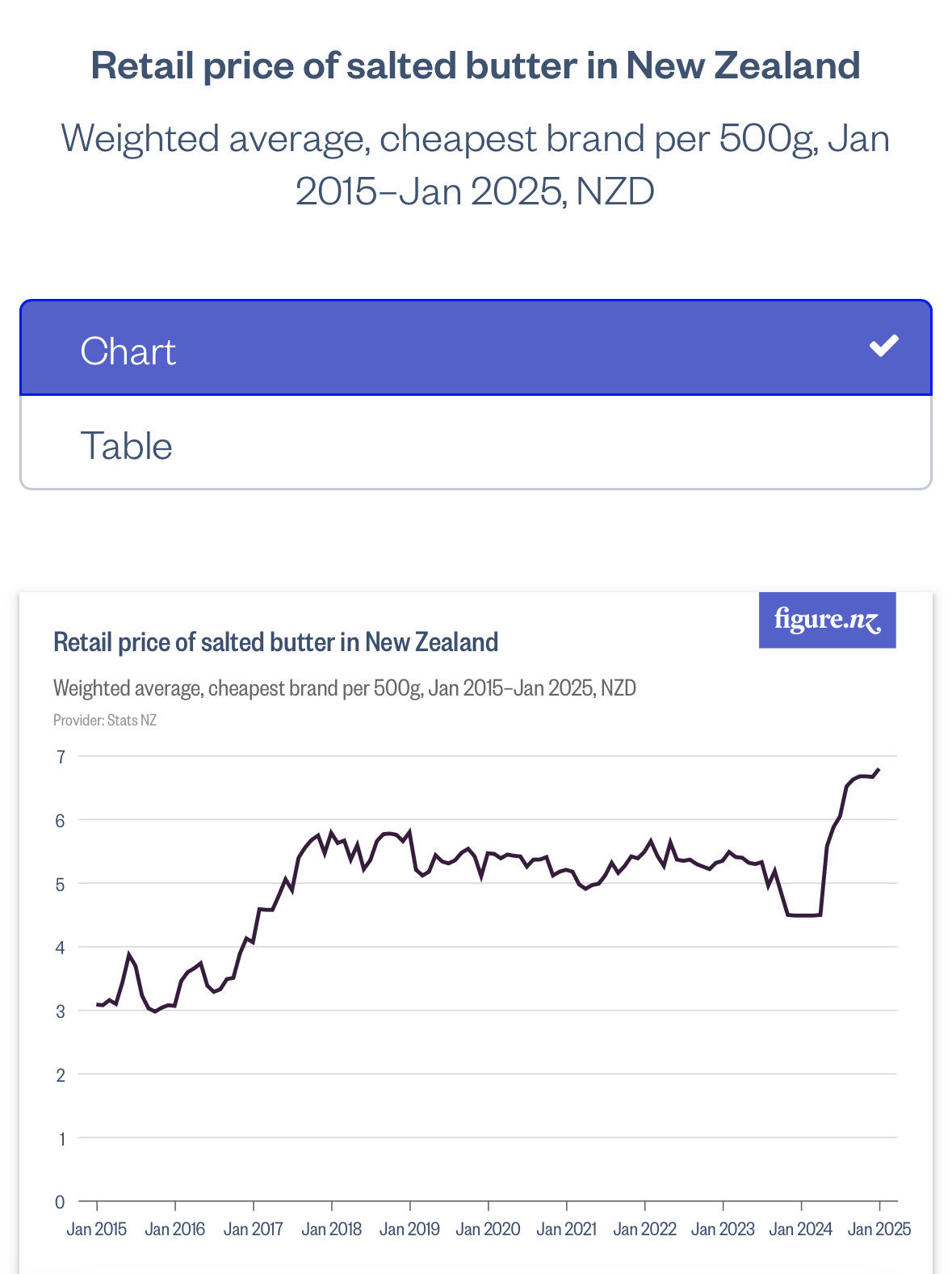

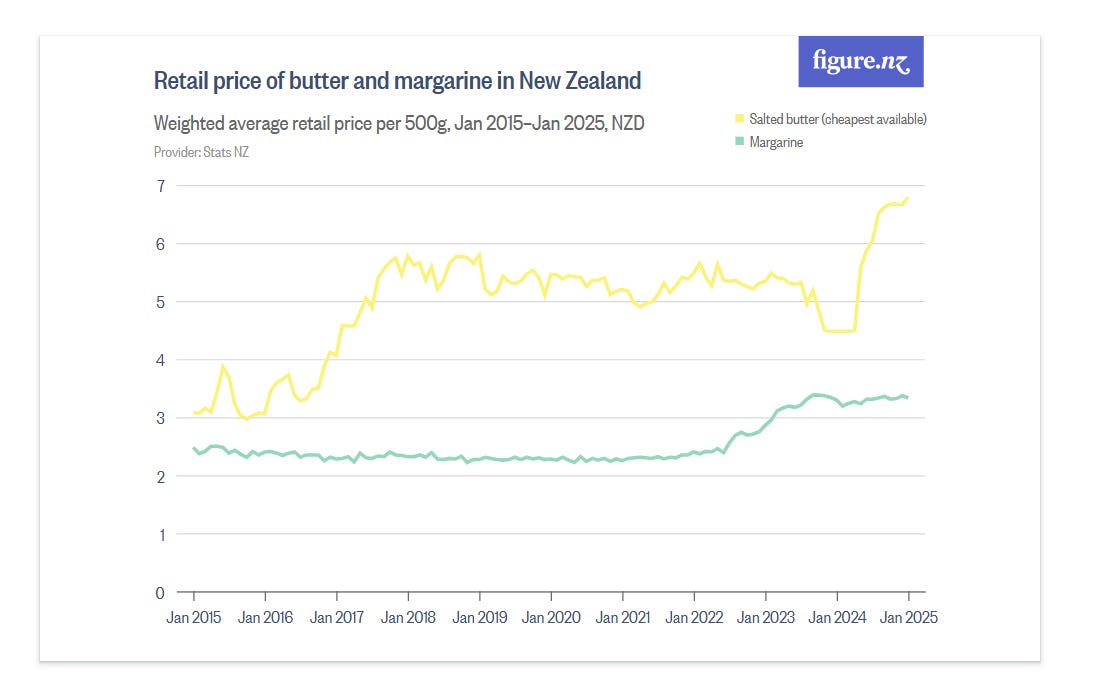

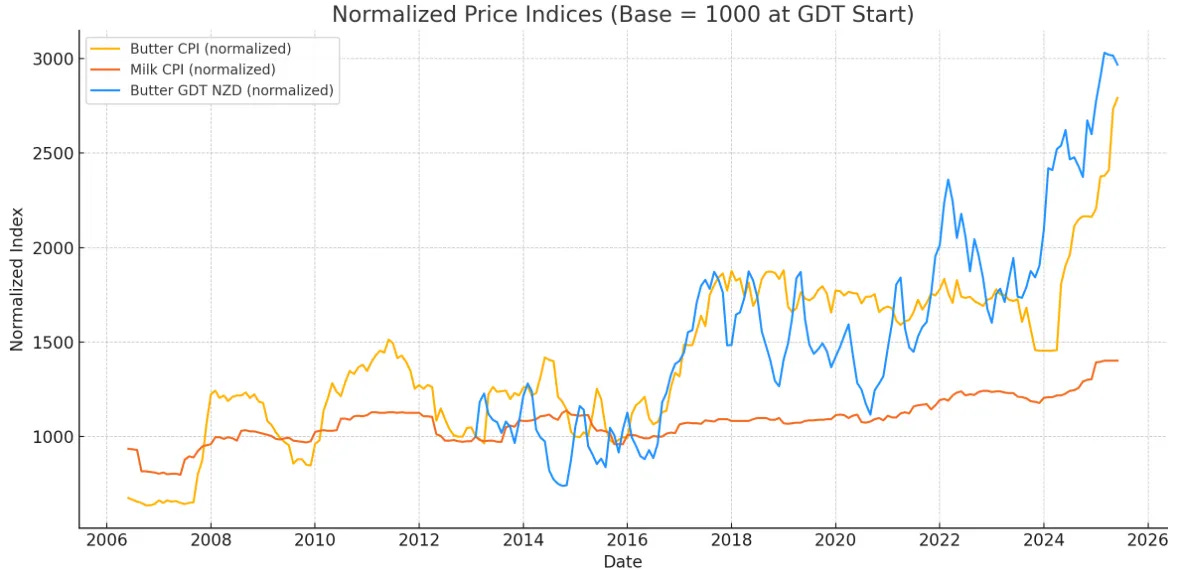

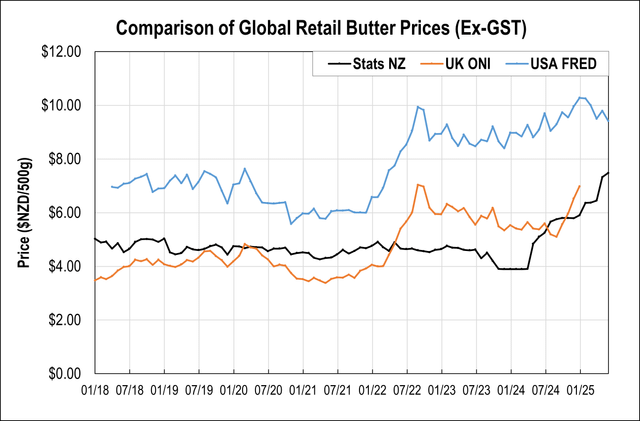

New Zealand has been more than happy to fill the gap left in the American butter market. In fact, commodity graphs suggest that their higher price may have actually been subsidising our lower butter prices towards the end of 2023. Or so I reckon, anyhow.

Regardless, that is not the case anymore. Low butter prices in New Zealand relative to global supply have caused mismatched price expectations between consumers and sellers, and the resulting spike has seemed even steeper due to how long the New Zealand price was kept low.

Because it has been kept low. At least, that’s what the statistics would suggest.

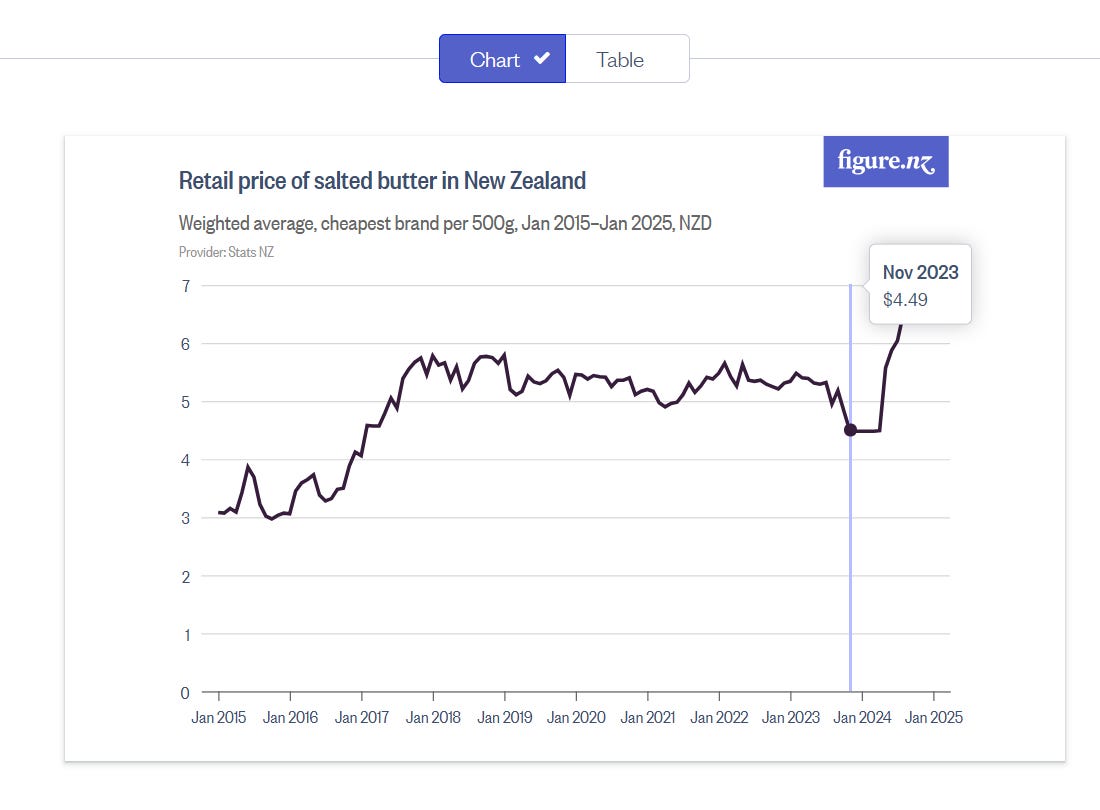

As National’s own campaign promo post points out (someone should tell them the election is still over a year out, by the way), NACTFirst took the reins and butter prices immediately flatlined.

Flatlined like they had been shot.

Flatlined like they had been price-controlled.

(Guess where on that graph the election was.)

That is the phenomenon the graphs appear to portray, to an amateur eye — my amateur eye.

A stock-standard, textbook demonstration of a price control, including the resulting price bounce back that is the very reason most sensible governments don’t use price controls to solve their problems.

It tends to create larger ones in the future.

But governments are not the only entity that can decide to match price controls

New Zealand’s butter prices have some small alignment with global trends at this time, albeit briefly.

America is an outlier; its butter prices drop around this period (but from a peak price they still haven’t returned to). Europe matches our low, but then shoots on out of it very early by comparison, settling at a higher price before continuing on a more stable path. Australia — right next door to us and in the same seasons as we are — mimics the European trajectory rather than ours, taking a short, unsustained dip down the dollar axis before climbing right back out.

For several months after this, our butter prices remain lower than all of them, at a gradient of zero.

Why?

Then that unnaturally flat line begins to climb, and we take several steps upwards to our current high rate. And I do mean steps. For this period, the flat lines remain unusually, unnaturally so, making it seem like they may have been curbed—or set—by a strong, specific market force.

At this time, Costco was selling Kirkland butter as a loss leader. Costco butter sits outside the Fonterra monopoly, sourcing butter from a former co-op and providing contract prices higher than Fonterra's in order to produce their branded butter, which was now being sold in New Zealand through Costco Auckland as well as overseas. Reddit tells me it’s becoming very popular with Americans, even more so than Kerry Gold. (And it really sounded like that meant something to them.)

But this competition was not what caused the butter stutter on the commodities graph, because their loss-leading policy began well before this date. The only thing this change coincides with precisely is the election.

Did Fonterra engage in price fixing in order to recognise the investment they made into NACT’s election win?

My first thought upon seeing this graph was “That’s really odd.” My second was, “Did Nicola Willis just admit to being involved in a dairy cartel? Surely not.”

I won’t say she was involved, especially when I have no evidence (other than her seeminly admitting it, I guess?) — but I will say, she doesn’t have to have been involved for this sort of deliberate price fixing strategy to work in Fonterra’s favour.

It is no secret that Nicola Willis has an employment history with Fonterra, or that NACTFirst likes to employ and be connected with the lobbyists of their donors, and then pass laws that seemingly go against the public interest upon getting into power that favour those connections and donors.

A lead example is our no-longer-in-effect smoking ban, a likely result of a tobacco lobbyist identifying Winston Peters as “very sympathetic” to them. Another is ACTs Nicole McKee, a former firearms representative, has used her political power to loosen our gun laws. And sitting around Luxon’s cabinet table, you will find a cesspool of qualified industry players whose previous jobs involved securing concessions for sectors and companies so they could profit more from the people of this country.

It’s no wonder questions of bias have dogged the coalition government everywhere they go. Wherever they stand, lobbyists have already laid the ground for them. Even in the case of our new medical school.

There’s been a lot of discussion lately about corporate influence and the ways politicians can affect market conditions for their supporters. But much less has been made of the possibility of such relationships working the other way around — instead of politicians writing policy to alter industries, industries can also implement policy to benefit politicians.

Especially if they have a monopoly.

Imagine this.

You are most of the dairy industry. You’ve just spent tens of thousands of dollars, hundreds of thousands of dollars, perhaps millions even, lobbying in preparation for the election. Not directly, of course — Fonterra has a policy of not making political donations, presumably to give the impression that they are politically independent or neutral (although anyone with their eyes and ears open knows this not to be so).

But your organisation has spent money pushing crucial messaging and other advertising and lobbying activities in an attempt to secure favourable trade winds for the future. Over this same period, most of your members have donated to the “right side” (literally) via other supposedly unrelated organisations like Federated Farmers, or under their own names.

In return for your investment, you have put into power New Zealand’s least qualified and competent Prime Minister/Finance Minister duo in history, including the one that was both and crashed the dollar as a result.

Their administration has not been very popular from the outset, in part because they’re the flavour of wet bread and also because they immediately started deconstructing democracy via executive overreach and using emergency legislation to pass the sorts of laws that give corporations power at the expense of the people, who only voted for them. They’ve also started a regime of austerity to pay for their unaffordable tax cuts that require dialling up our deficit during their term and beyond, and stealing money from the superannuation fund they’ve never contributed to. They are taking bold steps on things like making more people homeless and cutting funding from disabled people whose lives were improved by it, all to give back tax you’d rather “spend” yourself than receive in subsidised benefits because you believe in neoliberalism still, somehow.

This is all as you planned and expected.

National campaigned on cost of living, promising to bring prices down AND to provide more money to people, when in reality that was never going to happen; they were simply moving money around so the wealthier had a bit more of it.

And you are wealthy, in this scenario.

Or you think you are.

This is one of the weakest governments in history, leading a coalition held together by string and superglue. But before they crash and burn, as pundits and markets are predicting, there is a slew of environmental and economic legislation you still want them to pass. And you want people to like them more than they do, and you more too, and you know price control causes greater profits in the long run, and also what food means to a civilisation and a society.

What’s that other trick of Trump’s we saw used in the election?

Groceries.

Bread and circuses. And in this big tent, the politicians are the clowns.

It all comes down to the price of eggs. Or in our case, butter.

Internationally, profit has never been higher, while at home, prices around election time in 2023 were good (for the dairy/butter industry) but pretty uninspiring due to some untimely competition entering the supermarket arena recently. It would cost relatively little — and come with a lot of potential upside — to pause price increases across the board on an in-demand, staple good for a few months via your farmer-controlled monopoly, knowing that it will be more than made up for on the international market, and later domestically when prices are allowed to spiral upwards once more.

That spiral upwards is what we are experiencing right now.

Price controls, when lifted, create price spikes, like was seen in the infamous “Nixon shock” that forced him to re-freeze prices and, eventually, engineer a recession. This, too, is something Fonterra and its decision-makers will be aware of; losses during a short price freeze can be recouped afterwards during a resulting upwards spiral. Less profit now is acceptable if it creates more profit later.

That is what we are witnessing at the moment, and that’s why Fonterra are quick to pin the blame on the overseas market and not their usual excuse of ‘needing to get a return for farmers’ — if you look at their books, you will likely find that their profit margins are excellent. High prices become divorced from their costs when companies have the opportunity to make “excess profit”, which is why it takes so much time for inflation to stagnate an economy. At first, companies do make a lot more money, until resulting price rises from the vendors they deal with start to chew into their own bank balance, and their price setting becomes about recouping their own investments and preventing negative growth.

But that kickback is only for when it’s economy-wide. Individual industries are more sheltered from those negative effects.

Economy-wide after-effects of price controls were seen very recently in the post-pandemic labour shortages. The cost of goods had pushed up the price that people needed to be paid to survive. To fix this, Labour tied benefits to the minimum wage and raised it to meet inflation. That’s a price fix—a minimum price fix.

Raising minimum wage and benefits kept incomes increasing for our lowest-paid people, who spend every cent (and more) of their paychecks and who make up the bulk of our population. It ensured they could meet those rising costs, but unfortunately also meant that those costs then rose in turn for supermarkets and goods producers, who had themselves been so comfortable taking a few cents more for the products people couldn’t do without (at a time when they had more than ever before). And they weren’t so keen to let the good times slip away.

So the price of goods continued to increase.

Now our prices are no longer influenced by Labour‘s fiscal support and responsibility. National’s management of inflation during their term has not been to increase incomes to match, it’s been to remove them from the economy entirely. Wellington’s localised recession is like a diorama of the country, demonstrating in miniature what this government is enacting upon us all on a grander, slower scale. Canning public servants, cutting new initiatives, and cancelling infrastructure investments that were already planned and, in many cases, were contracted for has sucked all the cash out of circulation, and so people are less comfortable spending than they were a few years ago, even if they have about the same amount of money. And now they will force councils to do the same.

To encourage money to circulate still, National have made credit cheap again. Well, as best they can with an “independent” Reserve Bank. But this won’t have the same effect as it did the first time around when Labour did it. Post-pandemic, cheap credit was a delicious sugar hit that paired well with our record investment to get people spending loosely. Now they are feeling the effects, and it is winter (metaphorically), and cheap credit is being used not to splurge but to survive.

New Zealand has a debt-to-income ratio of 170%. The highest we ever reached was 175% over Covid. But that was when we had a government guaranteeing incomes; the wage subsidy meant people were confident money would keep flowing in even when the work didn’t, and so what followed was a shortage of workers rather than goods. It is the closest thing New Zealand and most of the rest of the world have had to a universal basic income, and it was followed by a period of peak employment that kept people feeling financially secure (and rightfully so), even if they also felt pressed by rising prices.

Now we have a government signalling austerity, even more of it than we’ve already seen. To meet their budget this year, Nicola Willis was forced to rewrite the OBEGAL to access our superannuation fund early. That money being spent poorly by our government has not gone to low-income earners and other spenders in the form of wages and services, but to landlords and the already well-off in the form of tax-backs and bright-line reductions.

That is the sort of money that doesn’t circulate.

The hope from Luxon and Willis is that private money will pour in to replace the money our government is no longer investing. But businesses tend to react opposite to how governments do during recessions; they tighten their belts. And a lot of what is spent in this belt-tightening is being spent on assets, largely on the trading of them, like stock buybacks or Luxon reducing his real estate portfolio.

Have you seen the price of gold lately? The commodity is increasing in value because more people are trading in it and speculating on it, notably because the people who buy gold are the ones right now with the money to spend, and because the rough economic forecasts say gold is going to keep going up.

But buyers are not “spending” it in a market sense. They are simply storing it in the commodity they think is most likely to outlast the financial storm the forecasts tell us is coming.

For New Zealand’s housing market with bits tacked on, our spare change down the sofas of our wealthy usually goes into real estate during downturns. But house prices are not as high as they used to be, which is very unusual here, and New Zealand home owners don’t quite know what to make of that — the line is only supposed to go up. And Luxon and Willis and Fonterra and all the rest are desperately trying to make it do that, including by opening our market up to flush overseas buyers who can pump up property values for the assets that have become too expensive for other New Zealanders to buy, like stations and largescale businesses.

Such values are only improved, they believe, by high dairy prices. It’s win-win-win for everyone. Except the consumer. But who cares about them?

This strategy benefits farmers too, whose largest asset will always be the productive land they own rather than the product they make from it. These farmers have likely borrowed money against that land. Cheap interest rates with an expensive property market is a much more profitable game plan (or retirement nest egg) than getting a few cents more on the price of milk for a few months.

Or on butter, for that matter.

Farmers and farming execs are not fools; they know the value of their holdings all too well.

And they vote — and act— accordingly.

So Nicola.

What exactly has been done to bring down the price of butter?

Excellent. Well written and easy to understand.

If there were a NZ butter manufacturer that only served the NZ market I’d assume that their costs would have increased by inflation and the cost of buying milk. But they’d be unconcerned with the International Selling Price of Butter and would have been willing to undercut Fonterra and gain market share.