Luigi Mangione, the shooter of the Ultimate Healthcare CEO, has been caught by the cops after a tip-off from a McDonalds worker. (A timely reminder, perhaps, that there is an official boycott against McDonalds for their profiting from and support of Israel’s occupation in Palestine, and it has been having an effect on them).

But Mangione’s ordeal has only just begun. Already he is fighting extradition to New York, where the shooting happened. It will be the first of a number of legal matters put before the courts that will determine whether he walks free, which is a potential outcome of this case.

This seems strange, perhaps — what defence does he possibly have to make? The police have found his ghost gun, they have DNA, video, photos… there is a very convincing trail leading from the shooting to this man. He even had a letter on him when he was arrested explaining why he did it.

But there is a chance — a real, significant chance — that he will not be convicted for this killing he definitely committed. Why?

Allow me to introduce to you:

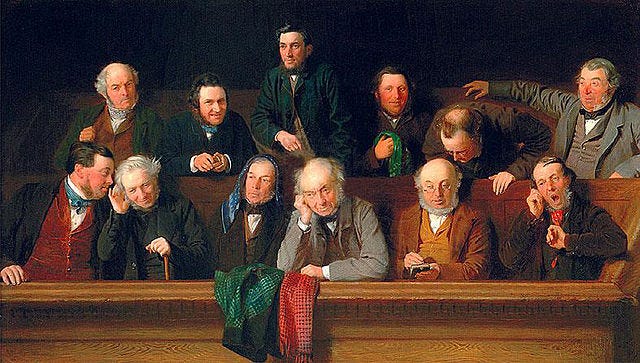

Jury nullification

Jury nullification happens when a jury refuses to convict a person of a crime they certainly, or almost certainly, comitted. There is no real legal loophole, no question as to the evidence presented that the act was carried out by the person sitting in the courtroom with them. But the jury votes not guilty anyway.

Why?

Juries are the barrier we in the Westminster system (and devolutions of the Westminster system, like Australia, America, and Canada) have established to protect us from unjust imprisonment and unfair laws. When the right to a jury trial was first granted to us, it was under the Magna Carter, and the aim was to prevent the King from persecuting his barons, who he’d just signed a brand new treaty with. The barrier to a conviction, the treaty decided, was a jury of their peers, and now is a panel of 12 or 13 people selected at random from the population to determine a person’s guilt or innocence.

This protection was meant to eke power away from the monarch; it was never intended to become the most fundamental right in the Western world and establish the doctrine of the Rule of Law. But that is what it did

Jury nullification can exist because the law protects jurists and their decisions, and their verdicts are usually binding and unchallengeable. A jury cannot be prosecuted or even really questioned for the decision they hand down, and the principle of double jeopardy usually prevents a person from being tried twice for the same crime. This means that a jury returning a not-guilty verdict usually guarantees acquittal for the defendant, even if their decision would be considered an “error of law” in an appeal court (had it been made by a judge in a judge-alone trial).

In this regard, by refusing to apply the law as it should be applied, a jury can “nullify” the law.

A pattern of verdicts like this can result in a law that exists but is not enforced; this is considered the mechanism by which the public maintains ‘final’ say over laws, simply by refusing to enforce them. Because convictions are handed down by the people, in theory, it is the people who enforce the law at the final level, and if the government passes legislation that juries refuse to apply, a precedent can be set such that it eventually negates the law in its entirety or can force a government to revisit, rewrite, or revoke overwhelmingly unpopular legislation. It is a useful and important check on the power of the state and a mechanism of democracy.

To a lesser or greater degree, individual cases of jury nullification are quite common throughout America and the Westminster systems. A famous example in New Zealand is the GCSB Waihopai prosecution, where a jury refused to convict three men for damaging a satellite after they argued their actions saved lives and were taken for the greater good.

New Zealand has an even more applicable example of jury nullification, one involving murder/manslaughter charges. In 2004, in Nelson, it took a jury just 47 minutes to find a father innocent of the murder and the manslaughter of his five-month-old daughter.

How a man walked away from murder

New Zealand doesn’t have a defence of diminished capacity.

It’s a stark weakness in our criminal justice laws that pops up in the news from time to time; most recently, it has led to the controversial trial of Lauren Dickason, who was found guilty of the murder of her three children after immigrating to New Zealand and becoming severely mentally unwell, resulting in her smothering them to death.

Without an ability to try someone for murder or manslaughter in a lesser capacity, to acknowledge that the wider circumstances or the defendant’s own impairments impacted their decision-making, New Zealand juries are frequently put in the awkward position of having to find defendants either fully guilty or fully innocent for the crime they are charged with. In the case of Lauren Dickason, they found her guilty despite her mental unsoundness. But for a father who had just learnt his daughter had an untreatable medical condition that meant her brain had never developed beyond the early fetal stages and who would have a short life of suffering post-diagnosis, the verdict was quite different.

In this case, the parents of a young baby had just learned their daughter had incomplete lissencephaly, the worst form of brain disorder she could have and still be alive. The father had been put under unfathomable stress in the process of getting this diagnosis and had supported his partner during and after they learned the news. Then when she had gone to bed, he sat with his daughter thinking about what this meant for her, for her future, for her life. He reported taking a handful of pills and straight whiskey with the intention of ending his own life, then running out of the house with his hand covering her mouth, smothering her. He was later found by police in the bushes, cradling her body, sobbing and telling them to “Leave them alone”.

He was described by the defence as someone who had needed to be there “for everyone except himself”. It was a sympathetic presentation that the jury were clearly deeply affected by. It was not difficult for them to see that this was not a case of murder, but a mercy killing by an irrational father who loved his daughter and had been pushed well past breaking point by her diagnosis and the confronting reality that she was essentially a vegetable, always had been, and always would be for the rest of her very short life. Her brain was a soup of unformed bits; she had never been able to see nor hear nor smile, and would likely die within months.

The law is about equity and justice. That is why we allow judges a great deal of flexibility in deciding sentencing in New Zealand; had the father in this case been convicted, I doubt he would have seen jail time for it.

But even a conviction, the condemnation of this killing that was not murder, not manslaughter, but the act of a desperate man in a situation no father should ever be put in, was not a just outcome here in the eyes of the jury. It was unconscionable for this father to be punished beyond how life had already punished him.

And I think, 20 years on from this court case, we can acknowledge that the verdict reached in this unfortunate, awful case was a just decision.

You can’t ask more than that of a justice system.

Nullification in the US

The United States’ tradition of jury nullification is a long and honourable one, and it has been used since its earliest days as a British colony.

In Britain in the 1600s, a group of Quakers had been acquitted for violating a law forbidding religious assembly; this is the shared origin of jury nullification that grants it precedent in former British territories. Doubtless with its strong tradition of religious freedom, this particular case appealed greatly to the American jury who first continued its tradition in the free land, when they quite appropriately used jury nullification to acquit John Peter Zenger of his charges of criticising public officials. After securing their freedom of speech, America then used jury nullification to avoid paying tax to the British.

Since then, jury nullification has been used effectively and often, for better and for worse, frequently acquitting murderers of black people and protesting prohibition charges.

Now in the 21st century, much of jury nullification centres around the injustice found in America’s drug laws — one advocacy group estimates that 3-4% of all jury trials involve jury nullification, and an increase in hung juries may also indicate that juries are grappling with the justness and equity of their laws and outcomes.

As such, Luigi Mangione’s trial will not be a trial that asks whether he killed the CEO of United Healthcare. It will instead ask whether it is fair to imprison, perhaps even kill via capital punishment, Luigi Mangione for what he has done. The outcome will depend not on the facts of the case, not on facts of law, and not on the “sympathies of the jury”, as the news will likely repeat ad nauseam.

It will be a question of justice, of fairness, and of equity.

What will be put on trial is not Luigi Mangione.

It is the American healthcare system itself.

what a totally BRILLIANT read. thank you. thank you.

Excellent Sapphi, a most interesting reminder of how justice can sometimes send verdicts that challenge the real narrative of capitalist society