The further you get into radicalism, the more appealing the concept of a revolution seems. Both the far right and the far left dream of taking up arms and overthrowing what they see as an unsatisfactory system, to an unhealthy and unhelpful extent.

Instead of revolution, what happens in the modern, western world is that times of social turmoil combine with increasing economic pressures to produce periods of rapid political and economic change. This is much preferable to revolutions; for a start, fewer people die. Revolutions also imply a total replacement of power, whereas rapid mandated change in a democracy allows the political scene to shift accordingly without needing to overthrow the state. This is good in a democracy, as a democracy has to be quite broken before it becomes moral to fight against it, and reforming the system must always be preferred to violence and the seizing of power through force.

Josh Drummond wrote an excellent piece today in Webworm about how heroism is the bane of collectivism, and it resonated with me. I was transported back to 2012, when The Hunger Games was the only book teenagers read, Les Miserables was playing alongside it in cinemas, and I was rapidly developing an obsession with the Easter Rising that would later morph into my autistic special interest in the Irish Republican movement.

I was 17, off to uni, and steeped in media where young protagonists stand up to against injustice and overthrow oppressive governments. I was also quite suicidal, giving the idea of sacrificing my life for a greater cause a heightened appeal. Neoliberalism (or as we called it back then, capitalism) and climate change made the future look particularly bleak, but the peaceful Occupy Wall Street Movement had failed. To my mind, nothing could be more glorious than the inevitable revolution and I would have signed up in a blink. The violence was just a means to an end, and a justified one.

I have a slightly more nuanced view of the world now. Revolution is war and, like all war, it causes economic devastation and the deaths of untold numbers of innocents, and then it causes deaths of innocents via economic devastation afterwards, too. It also requires a specific type of pressure and a heightened level of disenfranchisement that we in New Zealand would have had to devolve significantly to meet.

I was not unaware of that at the time.

But at 17, riled by the media I consumed, pressurised by the effects of Ruthenasia on my entire life and fuelled by a pessimistic outlook and poor mental health, that sounded like a good solution still. Necessary.

I guess you could describe my philosophy as ‘accelerationist’, which perhaps why I felt such a profound sadness over the death of Thomas Matthew Crooks, even more than I felt for his victims. He is a victim of the political climate, having literally spent his life from ages 10-18 under a Trump presidency. If that had been me, I might have tried shooting him too.

It is deeply alienating to rail against a power that makes you feel helpless and alone. There is very little we can achieve by ourselves — individual consumer choice is a myth sold to you by companies with bigger profits in mind. Oil companies paid for the idea of the ‘personal carbon footprint’ to distract us from effective actions to prevent climate change, and those actions can only be achieved as a collective.

But our collective actions, our small contributions, don’t always feel particularly satisfying, and it’s harder to find small labours fulfilling when you’ve been told all your life that change and heroism come from big deeds. Our society values individualism; capitalism and neoliberalism have pushed us to it. Public transport moves us from trains and busses into private cars. Profit is placed above social good. Family units become more solitary, tight-knit, and nuclear. Private property is valued more highly than collective ownership — people prefer not to share items between themselves as they become cheaper and resources more prevalent, mutualism becomes a countermovement, community assets are privatised, the corporate model dominates, and wages for workers at the bottom and middle of the ladder shrink while stock owners and executives take more of the pie. People who “become” financially successful are valued and respected more than people who do good.

But despite that, people who wind up financially successful are almost always those whose parents come from success.

(I struggle to understand the right-wing viewpoint that Luxon’s CEO background commands respect or at all qualifies him for the job. To me. that makes him considerably less admirable than your average retail worker. Not a statement about how much I value retail workers but instead of how little I respect CEOs.)

On my substack yesterday, Alma posted this enlightening comment that I think perfectly sums up who Luxon is. Someone who’s not clever enough to realise the damage he’s doing, and not humble enough to listen to the people telling him.

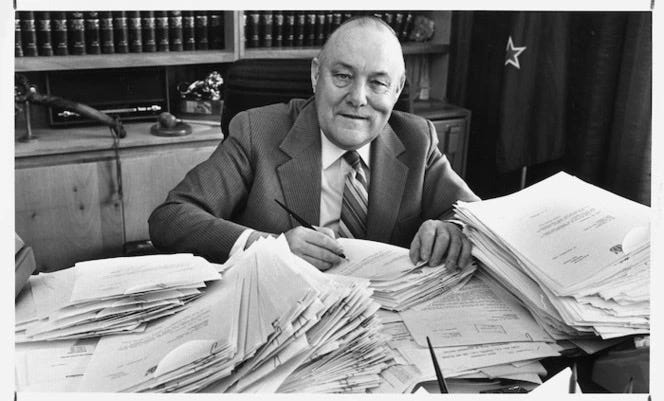

Remind you of anyone?

Unlike Muldoon, Luxon is interested purely in power and profit, and he’s not that fussy about what he has to give David Seymour and Winston Peters to keep it.

Somehow I’ve worked my way back around to Luxon-bashing again in this newsletter, but it’s just so easy to do. And it’s relevant to the topic given that Luxon is a perfect representation of this reality where businessmen fall upwards.

Corporatism and individualism — neoliberalism and individualism — go hand in hand. How else could companies achieve never-ending multiplication of value except by dividing us?

The ‘Luxon / Muldoon’ link is particularly telling! Although I think Muldoon, for all his arrogance, genuinely believed he was doing the right thing for New Zealand. As did Lange. I wonder where we would be had ‘Big Norm’ survived…

🙋🏽♀️Snap! Just read Josh's piece on Webworm, and, if you'll forgive the pun, it sent my mind down a worm-hole similar to yours. When it comes to Trump, the Secret Service may be taking the rap for falling down on the job with the attempted assassination & dead & injured bystanders, but I would be amazed if there haven't been other situations quietly handled & not publicised? On the other hand, people angry with him are mainly the less violent & "killing is the answer" types?

But honestly, I have wondered IF I had the chance to rid the world of him, could I/would I/should I take it? 🫢

As for Luxon, in my day there was a book that suggested "everyone rises to their level of incompetence" (The Peter Principle) and I'm sure it was based on Lux-flakes! Even with PM's in govts I didn't support in the past, they at least had some appearance of competence. Disagree about Muldoon tho' - he was a a misogynistic megalomaniac in my lived experience - it was my first introduction to politics as a young person & I saw no redeeming qualities in him at the time, or in hindsight 🤔