Why ACC’s $7.2 billion deficit is not what it seems…

The overlooked effect of interest rates and the collapsing health system.

The revelation of ACC’s $7.2 billion dollar deficit is coming at an amazing time for Luxon, Seymour, and Winnie. To start with, two of the three of them are engaging in a subtle war with the judiciary, in which ACT and New Zealand First have decided to prey on the lack of common knowledge of our common law system so as to present any judge-made law as inherently undemocratic (which is part of their wider attacks on the Treaty of Waitingi, of which much of the law has been defined and decided by the Waitangi Tribunal as per the statutory powers granted to them).

So an announcement that the courts have widened ACC’s remit to provide coverage for sexual abuse and foetal alcohol syndrome from the time it happens (in the latter example, from birth) and not from the date it was reported to ACC (for the former cases, that’s about ten years on average after the sexual assault took place) must seem like an unexpected windfall for both of them.

Except it’s not unexpected. It’s entirely to be expected, and is caused by the government’s own economic intentions to lower interest rates. It has happened with predictable regularity whenever this economic situation has arisen many times in the past. Here’s how it was explained then:

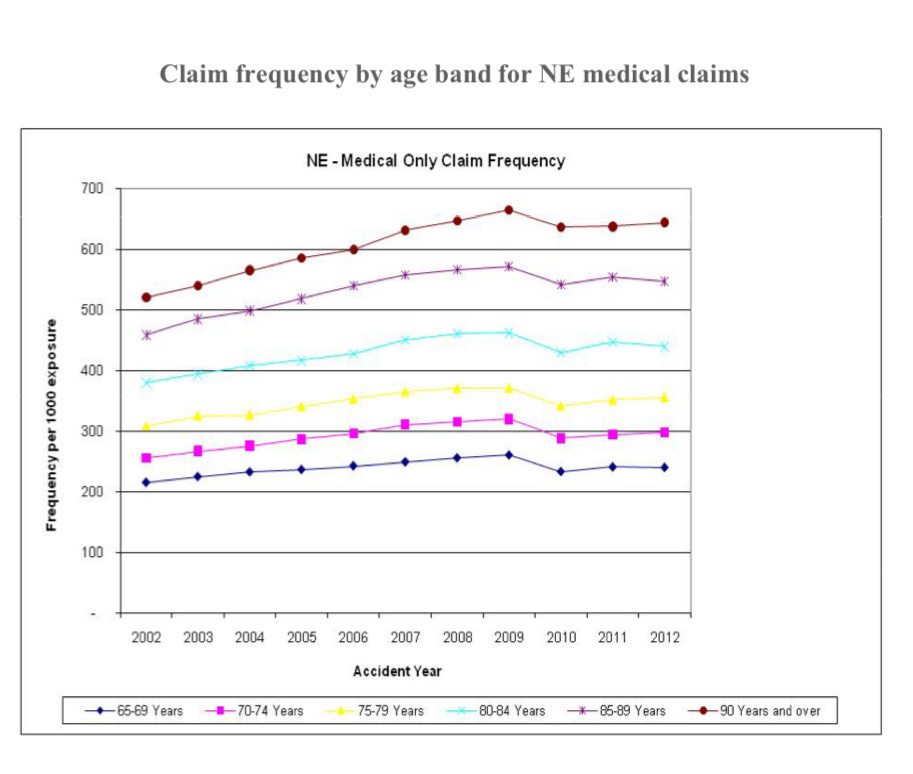

Low interests rates lead to a higher OCL, which estimates future ACC liabilities. While part of the current increased OCL is caused by this wider coverage (or should I say, this correct coverage as mandated by legislation that ACC has been deliberately stiffing victims out of for several decades), another major factor that affects the OCL is the dropping interest rates and ever-increasing costs of treatment. That’s why ACC’s own reporting from 2018 on the same phenomenon looks like this:

ACC are forced by statute to invest in bonds. When interest rate prices decrease, the value of their bond portfolios will increase — but this is massively offset by the impact on long-term liabilities that determine the OCL.

It happened in 2019, and was explained well by Dame Paula Rebstock at the time.

Note this graph, which shows large jumps in 2008 and 2011, coinciding with interest rate drops:

Then there is the other understated cause of these cost increases: more people these days are surviving their accidents, and more people are surviving overall. A combined mixture of an aging population plus better initial treatment outcomes mean that more people need longer rehabilitation.

For example, if you save the lives of dozens of volcano victims where many of them might have previously died due to lesser medical technologies, you are now on the hook for the recovery costs of more people, and those people with their skin grafts and intense rehabilitation needed will be very high needs and very financially burdensome. These people are also likely to be older on average due to our aging population, and old people need more care and are more expensive to treat.

This is a good thing, and is a fantastic example of why viewing health costs like you’re a CEO of a private enterprise is NOT. ACC and our public health system aren’t here to make profit, they are here to provide for the health of New Zealanders. Naturally, providing good healthcare will cause costs to increase as more people survive and as the population lives for longer and as we develop better (but often more expensive) treatments we want to make available to people to improve their lives.

For example, the World Health Organisation found a 17.6% increase from 2005 to 2015 in Years Lived Disability (YLDs) for health conditions associated with severe disability, and that a remarkable 75% of the total world’s YLDs in 2015 came from health conditions germane to rehabilitation. This is highly desirable, an incredible accomplishment actually, but obviously not from a financial perspective as it costs you more in the long term.

On the other hand, short term effectiveness of rehabilitation is declining. I would expect this to line up with trends that overall mental health is worsening — there’s a logical and well-proven link between overall mental health and recovery outcomes for all conditions. But there are other reasons as well, nationally and globally.

We must not reject out of hand the reality that ACC exists within a wider degrading health system. While this has created a haven of good treatment performed by private providers in a rehabilitative therapy system that is almost fully funded by our public insurance model, the initial treatment patients receive is being sabotaged by higher fees and longer wait times for public health resources like GPs and hospital treatments, as well as increased patient copays for things like physical therapy, which may see patients not adhere to their recommended recovery due to a greater financial burden. Altogether, these combine to provide worse outcomes overall and cost the system more.

The last time I was admitted to a hospital ward was back in about 2018, and I distinctly remember an elderly woman who had fallen and broken her hip. She was upset upon hearing from her doctor that she not only would not receive surgery that day, it was going to be a number of days before they could find her space in an operating theatre. This distressed her especially because she hated the idea of spending the night in hospital, a very understandable opinion when you’re not unwell, just in pain, and are experiencing a long and unnecessary wait in a noisy, bright, unfamiliar, uncomfortable environment.

I’m sure this mental strain did her recovery no favours, but even more alarming is how these increasing wait times in our system statistically contribute to poorer recovery outcomes across the board.

Long waits for GP appointments and higher GP costs that people may be reluctant to pay on initial injury inevitably cause delays to treatment at primary care level, leading to greater demand on hospitals, which in turn leads to longer waits for patients in those hospitals. ACC is delivered through this system while being unable to effect any change upon it, so the ill-effects of problems there will inadvertently cost the ACC scheme in addition to the financial burden it places on the general health system.

Here’s my personal example: I wasn’t provided sufficient mental health treatment by the public health system when I sought therapy in 2022. ACC, a system I did not initially want to use because of its adversarial nature and the fact that the conditions that I wanted treating, both I and ACC consider separate to my sexual assault, will now be footing a much higher bill that includes the effects of the harm done to me BY the mistreatment from the mental health system. It will also eventually probably involve me inquiring about how, because I am covered by ACC legally, I should have been receiving wage compensation while unable to work instead of being on the much-lower benefit. Not only will they have to meet those compensation costs (if I fight them for it — only 1% of sexual assault claimants since 2010 have received weekly compensation), I won’t have even had the benefit of receiving that higher income during that period, income that could have improved my recovery considerably. Receiving even 80% of minimum wage instead of benefit rates would have decreased the financial burden on me and made it easier to pursue more private treatments, and frankly, to do things that improved my life and my wellbeing, but that inevitably cost more money than someone on a benefit can justify to themselves.

Financial hardship has a proven, hugely-negative effect on mental health recovery and is considered both a cause and consequence of mental health issues, but notably income loss has a much greater effect on mental health than income gain.

Here’s my anecdotal evidence of mental health and financial means: I am writing this on holiday from somewhere off the coast of California where I’ve been searching, with some success, for my AWOL will to live, and have not only managed to improved my mental health but also have massively increased the amount of paid work I’ve been able to do, despite also being quite busy doing general fun touristy things. It’s a privilege I can only afford due to past savings from before my mental health plummeted, a refund from a fully-paid-for holiday I couldn’t go on back in 2023 because I was too suicidal to be at all safe on a cruise ship, a small h expected windfall, borrowed money from my very supportive and amazing family, and basically being a miserly person who has always been pretty squirrelly with money and good at saving/budgeting.

Oh, and also, as I’ve gotten better, I’ve been able to work more increase my income within the WINZ allowance of what you can earn above the benefit, which let me actually work toward and save for something meaningful and exciting, rather than just subsisting. That extra hundred dollars on top of the benefit has genuinely been the difference between “barely getting by” and being able to afford luxuries like this. And it turns out those luxuries are a little bit important when you’re trying to remember why you’re even alive.

It still sort of feels like a massive unnecessary extravagance, especially seeing as the only country I’ve visited before now has been Australia. But now that I’m nearly at the end of my holiday, I can conclude I wouldn’t be anywhere near well enough to do something like this if I hadn’t had something hopeful to work towards in the first place. Which does actually make it necessary, I guess, though it’s certainly still an extravagance, and there are so many people in my position who could never plan to do such things while in such a low place in life.

But things really just do keep sucking when you can’t afford to improve your life, or when it’s actively getting worse because you have less money now than when you were well. So slow recovery, delayed treatment, and resulting financial losses from injuries become a real problem for balance sheets, and not just of the person suffering the affliction.

This is true of the ACC scheme specifically too; while it’s by far our gold-star service for healthcare provisioning and public income insurance, that income insurance only comes at 80% of earnings, guaranteeing every person on it is put under financial strain, a strain which doubtless has a negative effect on overall recovery. This problem would have been solved by Labour’s income protection insurance which proposed topping this up to 100% in the event of injuries causing time off work — but alas, National and all the people they personally know can afford private insurance and have savings to fall back on, so the party of the rich and powerful simply didn’t see the need.

Lastly: burnout. Rates of burnout have increased greatly, and many people are finding working at a full time pace unsustainable, or barely sustainable. I suspect that burnout not only lengthens recovery time in a physical and mental sense, but people on ACC are seeking to actively extend this time in order to restore themselves and their mental wellness from the stresses caused by their job and by wider modern life that were weighing upon them before they even became injured.

When you ask someone on ACC how their time off is going, no matter how painful and slow their recovery from their injury has been, there is always expression of how much they needed the break. In lieu of mental health leave and sufficient sick day allowances (which have increased under Labour but National are looking to partially reverse) and proper employment support, ACC’s fully-funded time off is often a worker’s only chance to take sufficient time off to recover from employment overwork and mental burnout. So when the opportunity comes around, people naturally seize it with both hands and do not let go until their occupational therapist and overviewing doctor makes them return to to work.

I have a bad feeling about this reporting of ACC’s deficit, mostly because our Prime Minister already had them cut operational costs for no reason pertaining to them or their actual budget. But I’m sure that Luxon leaving them with little fat to trim will not prevent him from demanding more sacrificial meat from our most ambitious social support that saw away with the entire field of personal injury torts forty years ago, without which you would have to try sue someone each time you fell over.

Everyone thank Geoffrey Palmer that our billboards don’t look like this: